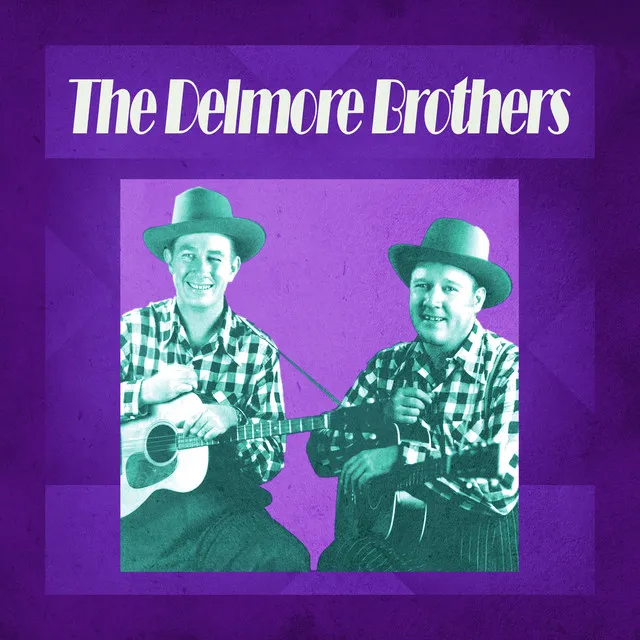

The Delmore Brothers are not nearly as well-known as such early country giants as the Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, Bob Wills, and Hank Williams. The reasons for this, upon close inspection of their work, are not readily apparent. They were one of the greatest early country harmonizers, drawing from both gospel and Appalachian folk. They were skilled songwriters, penning literally hundreds of songs, many of which have proven to be durable. Most important, they were among the few early traditional country acts to change with the times, and pioneer some of those changes. Their recordings from the latter half of the 1940s married traditional country to boogie beats and bluesy riffs, and in this respect they laid a foundation for rockabilly and early rock & roll, and rate among the most important white progenitors of those forms.

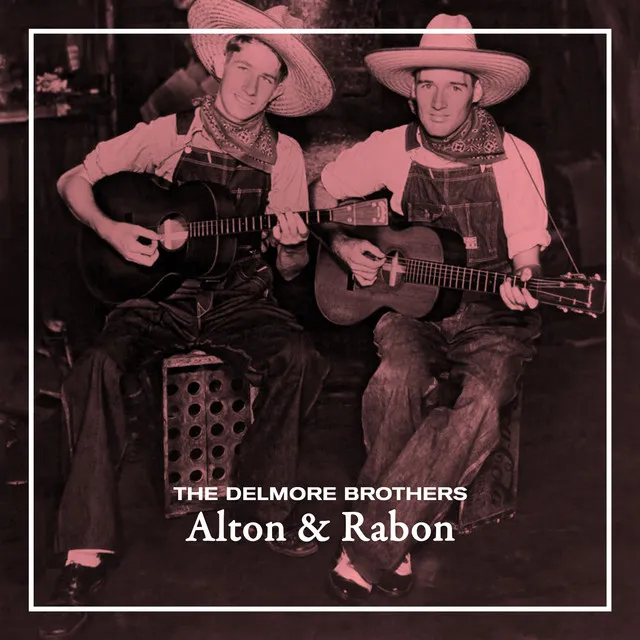

The Delmores were born into poverty in Elkmont, Alabama, the sons of tenant farmers. Alton would write most of the duo's original material, although his younger brother Rabon was also a competent writer. Performing on guitar and vocals from early ages, they were playing as a pair by the time Rabon was ten years old. In the early '30s, they were confident enough to enter professional music, auditioning for Columbia in 1931 and successfully auditioning for Nashville radio station WSM the following year.

Throughout the 1930s, the Delmore Brothers recorded often and performed on several radio stations. They probably gained their most early fame, however, from their long-running stint with the Grand Ole Opry between 1932 and 1938. The music emphasized their beautiful soft harmonies, accomplished guitar picking, and strong original compositions. Unusually for that time (or any other), the Delmores would switch high and low harmony parts from song to song (or even within the same song), although Alton would usually sing lead. Whether performing their own songs, traditional ones, or gospel, they brought a strong bluesy feeling to both their music and their vocals. It's that element, perhaps, that enables the Delmores, more than many other acts of the time, to speak to listeners of subsequent generations. Not to be underestimated either are their down-to-earth lyrical concerns, which address commonplace struggles and lost love with grace and redeeming, good-natured humor, rarely resorting to cornball tears.

In 1944, the Delmores signed with King, inaugurating an era which found them delving into and innovating more modern forms of country. Although their first sides for the label stuck to a traditional mold, in 1946 they expanded from their acoustic two-piece arrangements into full-band backup, with bass, mandolin, steel guitar, fiddle, harmonica, and additional guitars. Some of those additional guitars were supplied by Merle Travis, who credited Alton Delmore as a key influence.

In retrospect, however, the most important backup musician on these sides was Wayne Raney, who played a "choke" style of harmonica that was heavily influenced by the blues. The Delmores were also leaning increasingly toward uptempo material that reflected the upsurge in Western swing and boogie-woogie. By the end of 1947, they were also using electric guitar and drums. Raney (who also sang) in effect acted as a third member of the Delmores in the late '40s and early '50s, when they plunged full-tilt into hillbilly boogie.

These are the most widely available and, in some ways, best Delmore Brothers sides. They were also the most successful, and in the late '40s the brothers reached their commercial peak, releasing a series of hard-driving boogies with thumping backbeats and bluesy structures. Arguably they milked the cow dry, recording "Hillybilly Boogie," "Steamboat Bill Boogie," "Barnyard Boogie," "Mobile Boogie," "Freight Train Boogie," and even "Pan American Boogie."

These were usually exciting performances, though, featuring extended guitar solos that clearly looked forward to the rock era. Listen, for instance, to the lengthy guitar breaks of "Beale Street Boogies" (unreleased at the time) -- very few, if any, white or Black artists were riffing so extensively in 1947. And of course "Beale Street" itself was a tribute to the most famous musical street in Memphis, the city that did so much to cross-fertilize Black and white roots music into what became rock & roll.

The Delmores didn't stick entirely to boogies during their King era, also releasing some slower bluesy material. One of these, the original "Blues Stay Away from Me," became their biggest hit, and indeed the most famous Delmore Brothers song of all, often covered by subsequent country and pop artists. Interestingly, the Delmores continued to record gospel on the side, as part of the Brown's Ferry Four, a quartet which also included (at various points) Grandpa Jones, Merle Travis, and Red Foley.

As influential as the Delmores' King sides may have been on the future of American pop, the Delmores themselves would not be able to capitalize on that future. By the early '50s, their commercial success was fading. After the death of his young daughter, Alton drank heavily; worse, Rabon died of lung cancer on December 4, 1952. Alton (like longtime accompanist Wayne Raney) did record some material as a solo act, in both the gospel and rockabilly fields. Alton was way too old to begin a new career as a rockabilly singer, though, and he didn't record much for the last decade of his life. He wrote the autobiography Truth Is Stranger Than Publicity (published posthumously in 1977 by CMF) before dying on June 9, 1964. By that time, the Delmore Brothers' work had already proven extremely influential, particularly on the harmonies of fellow sibling acts the Louvin Brothers and the Everly Brothers. They left behind an extraordinary lengthy and consistent body of recorded work -- virtually none of their sides are lousy, at least the ones which have been reissued. Much of the Delmores' early material can be hard to locate, although many of the King sides have become reissued. ~ Richie Unterberger, Rovi