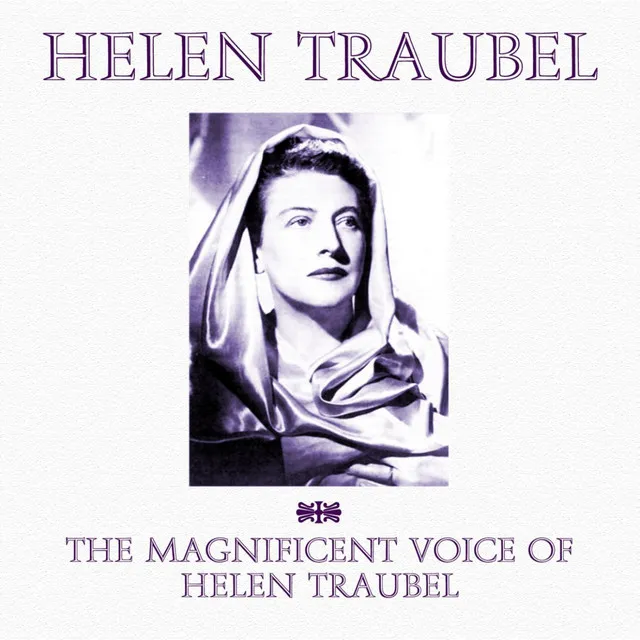

Helen Traubel emerged as a major talent when she shouldered most of the Wagnerian heroic soprano roles at the Metropolitan Opera when Kirsten Flagstad and other European-based singers became unavailable in the early 1940s. But her rise to fame was not predicated only on having an open field; her immense, vibrant, and warm-toned voice and thorough schooling would have made themselves known in even the most competitive circumstances. Traubel came to the Met almost reluctantly, having declined earlier offers; she waited until she felt herself completely prepared. Despite a shortness in the top-most register which caused her to duck her high Cs, she was an imposing artist, both physically and vocally. She retired from the Metropolitan and most other stage work only when Rudolf Bing, then the manager of the Metropolitan, objected to her appearing in nightclubs (thus following her frequent partner, Lauritz Melchior).

After long-term voice study with Louise Verta Karst in her native St. Louis, Traubel made her debut as soloist with the St. Louis Symphony in 1925. During the ensuing decade, she performed as a concert singer and recitalist, also appearing often in radio broadcasts. In 1937, Traubel was engaged for the role of Mary Rutledge in Walter Damrosch's The Man Without a Country during a second spring season at the Metropolitan Opera. Notwithstanding her inexperience on stage, she exhibited a lustrous, voluminous sound and considerable dramatic presence. The opera was not well-received, but Traubel's performance was warmly praised. Despite the tepid reviews, the opera was granted a solitary performance during the following February, but with Flagstad and Marjorie Lawrence on the roster, Traubel received no call to sing the repertory for which she seemed destined.

During 1938, Traubel largely withdrew from concert activities in order to prepare an operatic repertory. An October 8 New York Philharmonic concert performance of the Immolation Scene in 1939 so stirred the audience that she was asked to repeat it in another symphony series. Finally, after having twice turned down the Metropolitan's offer of Venus as unsuitable, Traubel was assigned Sieglinde and made her Wagnerian stage debut on December 28 with Flagstad, Melchior, and Schorr. In spite of her limited acting abilities, her sumptuous singing and personal warmth made a singular impact. An Elisabeth in a February 1940 Tannhäuser was also wonderfully sung, if somewhat ponderous in action. Within a year, Traubel's two soprano colleagues would no longer be at the Met, Flagstad having returned to Norway for WWII's duration and Lawrence having been stricken with polio. At that point, Traubel became indispensable to her company, left to carry on with Wagner, aided only by a very young Astrid Varnay.

Meanwhile, the 1940 - 1941 season offered Traubel relatively little. Her Walküre Brünnhilde was not ready by performance time, so she was left with several Sieglindes. During 1941 - 1942, Traubel was the Brünnhilde when Varnay made her spectacular December 7 debut as the Wälsung sister, and in February she offered a strong Götterdämmerung Brünnhilde, reserving her most powerful and accomplished singing for the final act. For the 1942 - 1943 season, there were advances in her ease on stage as well as splendid singing as Isolde and the Siegfried Brünnhilde (both, however, shorn of the top Cs).

With Melchior and the younger Set Svanholm, Traubel held high the German standards at the Metropolitan during the wars years and beyond. When Flagstad finally returned after her long absence, she insisted on sharing her repertory with Traubel, an artist she greatly admired.