Charles Alexandre Lecocq was the composer of some of the finest of French operettas.

He came from a poor family. A birth defect deformed his hip, forcing him to use crutches for the rest of his life after he was five years old. He found music a field that consoled him and in which he could excel. He began playing the flageolet when he was not much older than five, and soon had taken on the piano. By age 16 he was so proficient that he was giving lessons. He studied harmony privately with Crevecoeur.

In 1849, at the age of 17, he entered the Paris Conservatoire. His harmony and composition teachers were Bazin and Halévy. Among his fellow pupils were Camille Saint-Saëns and Georges Bizet. At the end of the term in 1851 he was second prize in counterpoint and ranked highly in Benoit's organ class. However, his weak legs made playing organ pedals unduly difficult for him.

In 1854 he had to leave the Conservatoire without graduating so that he could work to bolster the family income. He gave piano lessons and served as a rehearsal, class, and private lesson accompanist for the ballet master Callarius.

In 1856 Jacques Offenbach, as a publicity event for his operetta company at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiennes, put on a composition competition. Entrants were given the libretto for a comic opera, Le Docteur Miracle. Bizet and Lecocq shared first prize. It was whispered that Halévy had rigged the voting to favor Bizet, and Lecocq ought to have won outright. Offenbach acted strictly impartially, and gave the operas 11 performances each.

This was enough publicity to get Lecocq some jobs writing one-act operettas, usually intended as curtain-raisers. These low prestige pieces got him little attentions; if the opera company's evening was successful, this would be chalked up to the item on the main fill. Lecocq wrote seven of these little pieces from 1859 to 1868.

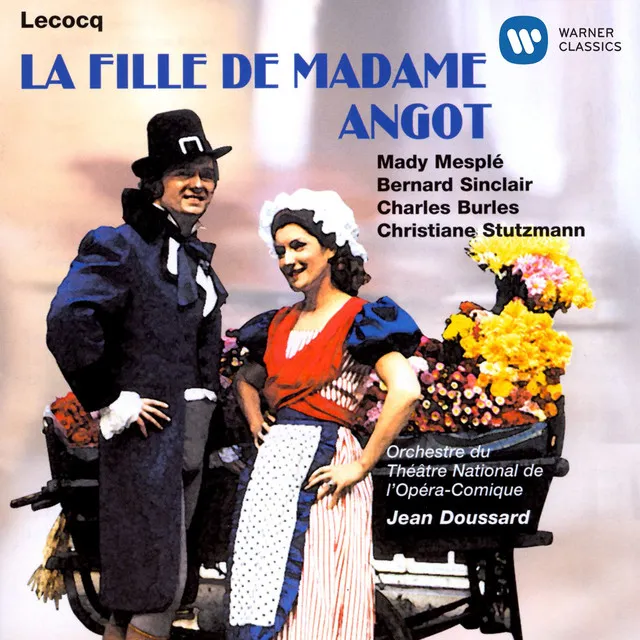

Finally he had a break-out hit in an operetta called Le fleur de thé (The Tea-Flower) in 1868. The audience loved its exotic Japanese setting. But international events impeded his ability to follow up this success. War with Prussia threatened. Lecocq prudently retreated to his ancestral homeland, setting up in Brussels. There his Parisian fame enabled him to stage three popular successes in a row, Les cent vierges (1872), Le fille de Madame Angot (1873) and Girolflé-Girofla (1874). Their success in Brussels was enough to make Parisian impresarios want to stage them (once the War was over) and they all went on to popularity in France.

He was regarded as the successor-apparent to Jacques Offenbach after he wrote two new hit operettas for Paris, La petite mariée and Le petit duc in 1875 and 1878. He ended up writing over 40 stage works, some of them quite popular but none matching the lasting success of the ones already mentioned, which include items that still are in the French operetta repertory. He attempted a full-scale grand opera, Plutus, but it was a failure. He gradually eased into retirement as he realized fashion had passed by his style of work. He wrote a few orchestral pieces, chamber works, and choral music for a convent. Some of his piano pieces and songs use the pseudonym "Georges Stern."

Lecocq's lighter music continues to delight with its fine lyrical content and deft use of rhythm to propel the comedic situations.