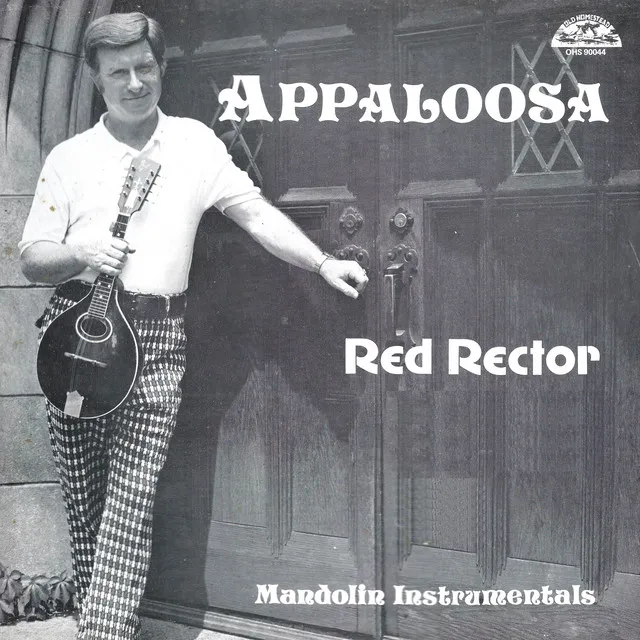

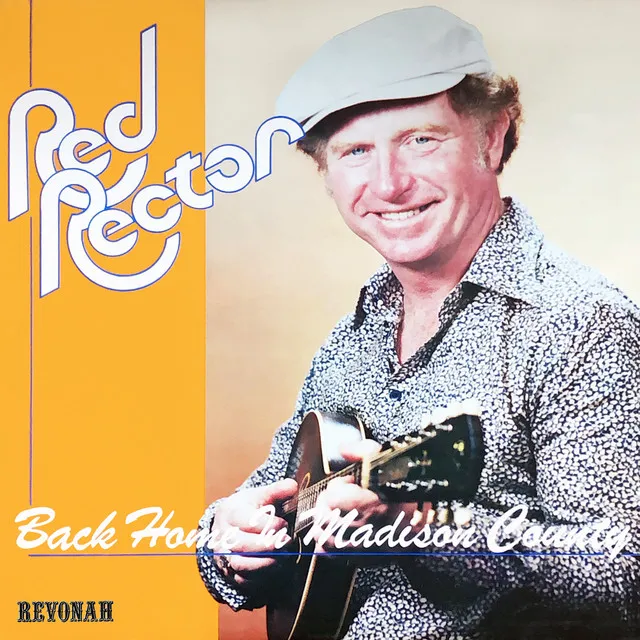

Based for most of his career out of Knoxville, TN, Red Rector was one the great second-generation traditional bluegrass mandolinists, which means, for one thing, he grew up listening to the sounds of Bill Monroe. In his playing, there were almost as many individual strengths as there are strings on a mandolin. He was known for a durable sound that could cut through whatever ensemble he was in, even when a dynamic banjo player such as Don Stover was trying to drown him out. In a music the uninformed listener might associate with "hicks," Rector played with a musical sophistication that could make a hip jazz musician or studied classical virtuoso's ears stand at attention. He could make an audience laugh with a mandolin solo, although he never got as deeply connected with humour in music as his fellow mandolinist Jethro Burns. His playing could be as precise as a triple scale session player, and as sincerely sentimental and moving as any mountain musician picking a tune on someone's front porch. And, boy oh boy, could he ever play fast! When told by one interviewer that his solo on "Blackberry Blossom" sounded like it was going at 6,000 miles an hour, Rector calmly corrected him: "Maybe a little faster."

Born Eugene Rector in North Carolina, his early listening experience was dominated by the popular sounds of Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys. He was so quick to want to become a mandolinist that he was even picking away on the little instrument for something like three years before he knew how to properly tune it. Besides wanting to master the complicated art of tuning, his main motivation was to sound just like Monroe. At 15, Rector was already playing in a group called the Blue Ridge Hillbillies, which featured guitarist Red Smiley and fiddler Jimmy Lunsford. He even got some personal advice from his idol at a festival where both their bands were appearing, Monroe telling Rector that his wrist was too stiff. In late 1946, Rector went on tour with the old-time duo Johnny and Jack, having worked all year on loosening his wrist. Now he was a bold and brave sweet 16, and the older musicians around him began to try to assert some influence over his playing, steering away from copying an established star and encouraging him to instead develop his own playing style. Rector resisted this advice mightily, believing that there was only one way to do things on the mandolin, and that was the way Monroe had done it. In this way, one of the many jokes in the "musician meets burned out lightbulb" genre could have been made up about Rector. How many bluegrass musicians does it take to screw in a lightbulb? A: Fifty. One to do the job, the other 49 to tell you how Bill Monroe would have done it. Rector's bandmates kept up the pressure, trying to tell him about one mandolinist they knew about who was fixing the lightbulb, so to speak. That was Paul Buskirk, a West Virginia mandolinist who had indeed developed his own concept. When Johnny and Jack finally scored an invite to play on the Grand Ole Opry, the young mandolinist was so frightened at the prospect that he refused to play, meaning the old-timers went ahead and hired this Buskirk fellow to replace Rector for this high profile appearance. This was when Rector actually got to hear Buskirk for the first time, since he tuned in to the program to see how the boys would do without him. To his surprise, the mandolin playing of his replacement had an even stronger impact on him than Monroe's had. Rector rethought the idea of developing another mandolin style, since he now saw clear evidence that such a thing was possible, and that lightning bolts aimed by Monroe would not come blasting out of the sky. He first did what most young musicians would do in this situation: attempt to create a new style by fusing his Monroe imitation with whatever he could pick up from Buskirk, especially his more intense use of notes on the low strings. But he steadily began absorbing the work of other mandolinists as well, now that his ears had been opened to the idea. Ernest Ferguson, who picked with the Bailes Brothers band, was another formative influence on Rector's picking style.

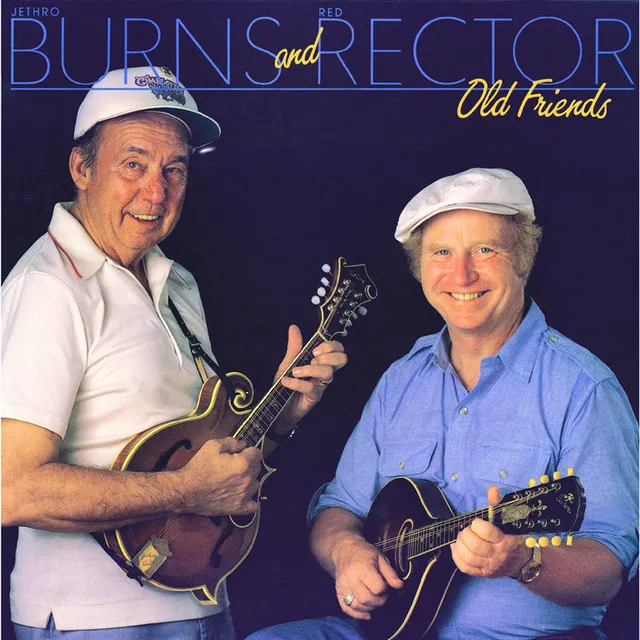

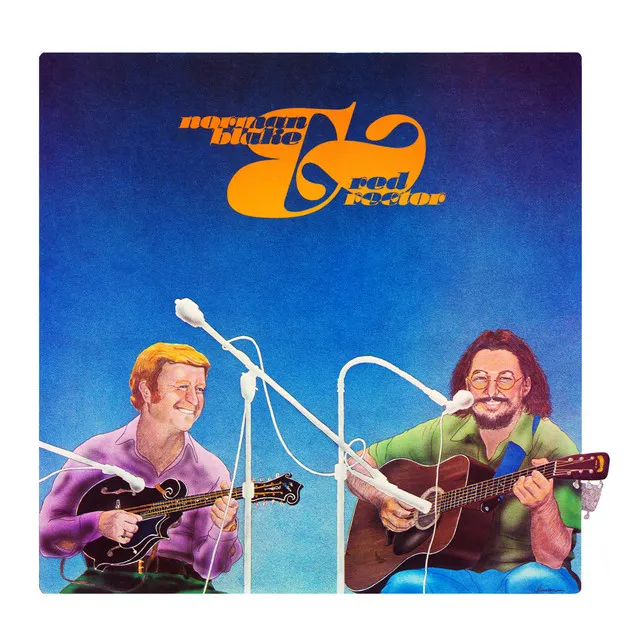

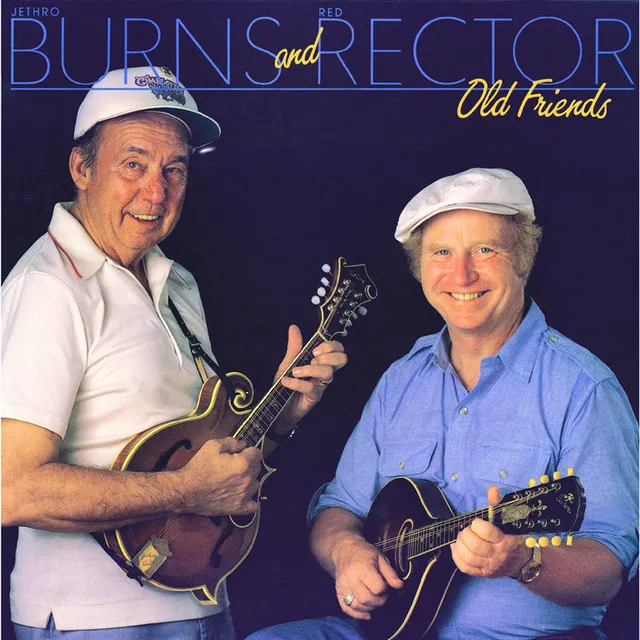

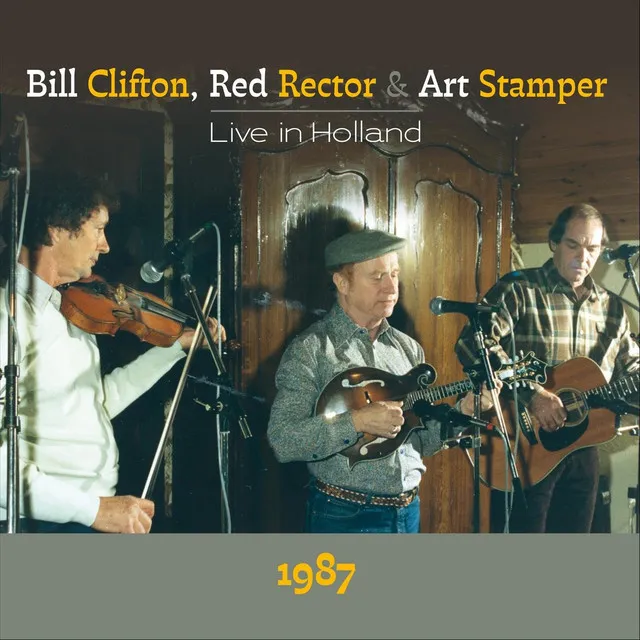

Rector relocated to Knoxville, TN, as the result of a new job with Charlie Monroe. One of the first concerts he went to there was a performance by the bluegrass comedy duo Homer & Jethro, which, needless to say, introduced him to the mandolin artistry of Jethro Burns. Putting all the pieces together, Rector recalls that by the age of 18, he thought he had finally gotten his own style of playing together. That much is plainly evident from the ample documentation on record, with artists such as flatpicking whiz Norman Blake, banjo man Bill Keith, fiddler Kenny Baker, and the previously mentioned Don Stover, with whom he toured England in the '80s. Mandolin lovers are particularly fond of the album Old Friends which he recorded with Burns for the Rebel label. But well before this type of artistic triumph from his mature years came more than a decade of honing his talents with early traditional bluegrass outfits such as Hylo Brown & the Timberliners and the co-operative band led by banjoist Don Reno and Rector's old buddy Red Smiley on guitar and vocals. The mandolinist worked off and on with the latter outfit between 1951 and 1959, much of the material collected on a CD box set released by the King label in 1996. Of course, when the city of Knoxville created a mural dedicated to the players who had come out of its rich musical traditions, Rector was given a prominent spot. In that city he is also remembered for his local activities, such as the bluegrass comedy duo Red and Fred, as well as appearances on the Knoxville television series the Farm and Home Show. Erudite listeners who might be taken aback by this type of exposure, bordering on the Hee Haw mentality, can balance it out with an equally strong academic quotient to Rector's legacy. His mandolin performances have been the subject of a doctoral thesis, as well as articles in scholarly journals with titles such as Mandolins and Metaphors: Red Rector's Musical Aesthetics. But Rector never became overly stuffy about his achievements or place in bluegrass history. He even calmly put up with being introduced as "Red Rectum" by the multi-instrumentalist songwriter and old-time music enthusiast John Hartford, with whom he recorded tracks for the 1971 Warner Bros. album Aeroplane, later reissued on CD by Rounder. ~ Eugene Chadbourne, Rovi